The Society for the History of Collecting

are delighted to invite you on

16 November 2023, 6:00 pm (GMT); 7:00 pm (CET); 1:00 pm (EST); 10:00 am (PST)

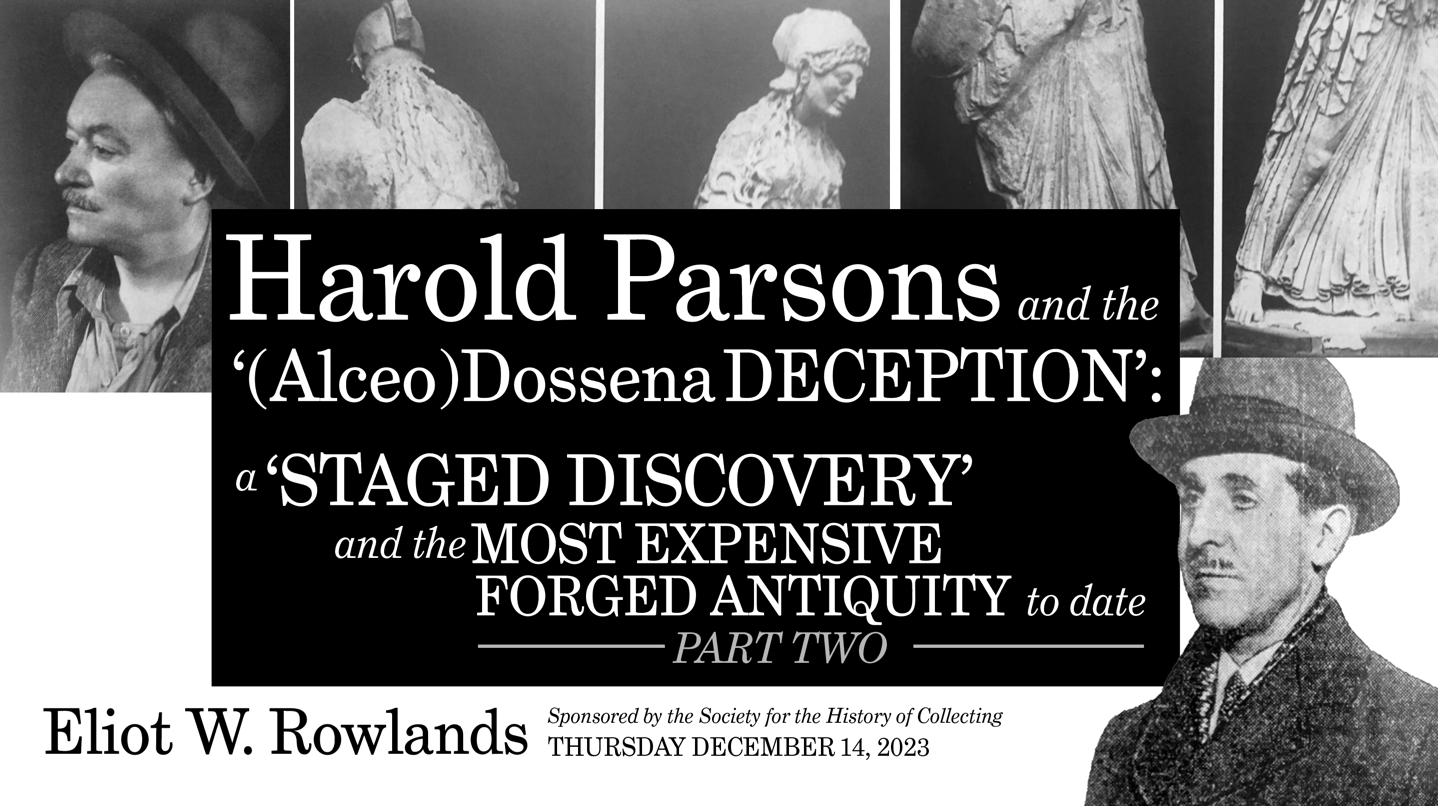

for Part 2 of Eliot Rowlands' lecture

According to the American art agent, Harold Woodbury Parsons (1882-1967), Alceo Dossena (1878-1937) was “the greatest forger who ever lived” and, without doubt, in the medium he chose—sculpture—he retains that dubious honor. Beginning around 1921, collectors and art museums in America spent a huge amount, some one million 1920s-dollars, for Dossena creations. (Among the buyers were Helen Clay Frick and such institutions as the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Cleveland Museum of Art, for which Parsons served as an otherwise very effective adviser in purchasing European art.) Parsons was burned twice, especially badly in the case of his second purchase, a just over six feet, pseudo-Archaic Greek statue of Athena. This was arguably the costliest Greek or Roman forgery up to the time and was acquired from a very reputable source, the Swiss dealer, Jacob Hirsch.

The details of how each statue was acquired by the Cleveland Museum, had been previously authenticated and was then exposed will be recounted in this talk, which is partially based on new, unpublished sources. Dossena received a fraction of the money garnered by the scam’s two masterminds, yet the sculptor’s innocence cannot be assumed.

In discussing the Cleveland Museum of Art’s first Dossena purchase, an almost eight-foot high, wooden Madonna and Child, we encounter the German-born, American museum man, Wilhelm R. Valentiner, who attributed the work to the Trecento master, Giovanni Pisano—whereupon, some two years later, he declared it modern. By 1926, both he and the Vienna museums’ sculpture specialist, Leo Planiscig, recognized that this and some other twenty other works were all by the same unknown hand. One year later, the forger’s identity was revealed, to the fury of both the buyers and sellers of Dossena’s art.

Of the wronged parties, only Parsons succeeded in getting his museum promptly and completely refunded, either with a substitute work of art, in the case of the so-called Giovanni Pisano, or (as with the Athena acquired from the agent’s occasional business partner, Jacob Hirsch) with payment returned in full. Following World War II, however, Parsons—by now obsessed with “outing” fakes—caused rifts with American museum professionals, leading to increasing marginalization in later years. This development is in contrast with his essentially effective record, working as a talented and resourceful go-between before the war for museums, dealers and collectors.

***

Eliot W. Rowlands is a New York-based, independent art historian, specializing in early Italian painting and the history of collecting in America. He earned his Ph.D. in 1983 from Rutgers University, with a dissertation on Fra Filippo Lippi, and was an Associate Fellow at the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies at Villa I Tatti, Florence, in 1985–86. He was a curator at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art from 1986 to 1993 and was senior researcher at the international firm of Wildenstein & Co. for over twenty-five years. Among his publications are The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: Italian Paintings, 1300 to 1800 (1996); Masaccio, Saint Andrew and the Pisa Altarpiece (2003); as well as numerous scholarly articles. He is currently engaged on a book on Harold Woodbury Parsons, who served as the agent for European art for several midwestern museums (including the Cleveland Museum of Art and The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art), as well as a host of private collectors. For the latter project he received a Leon Levy Senior Fellowship from the Center for the History of Collecting at the Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library (2017); a travel grant from the Francis Haskell Memorial Fund (2022-23); and a Franklin Research Grant from the American Philosophy Society (2023).